Desire & Punishment Film Series

A series on Fascism curated by filmmaker Amalia Ulman.

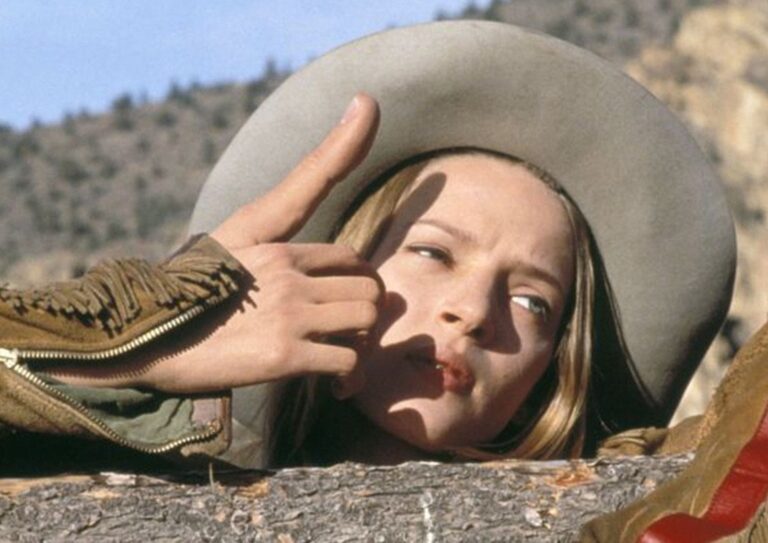

Scene from The Holy Girl

Desire & Punishment

A series on Fascism curated by filmmaker Amalia Ulman including the following titles:

The Holy Girl – Lucrecia Martel (2004)

If…. – Lindsay Anderson (1968)

The Piano Teacher – Michael Haneke (2001)

The Executioner – Luis García Berlanga (1963)

__________

Words by Amalia Ulman

I love America. I love America the beautiful because she’s still young and naïve and drunk with opportunity. But like a beautiful teenager (who everyone wants to fuck) she says a lot of stupid things (that everyone chooses to ignore). It is her ignorance that makes her cool, fresh, unconceited. La ignorancia es atrevida, we say in Spain: ignorance is daring. During the past few years there was a trend (hopefully dying out) that really tried to make fascism seem cool, based. But like everything America touches, these ideas of fascism, Catholicism and monarchism are Disneyfied caricatures of the European originals. A girl wearing a holy trinity bikini set.

It’s funny to imagine fascist repression as something colorful, but here we are. To me fascism is gray, claustrophobic, and heavy on the chest, like the moments before a summer storm. That very moment when the air smells bad.

I spent my childhood in a Spain still adapting to democracy after forty years of fascist Catholic dictatorship. Although they were closeted, many fascists were still around – about half of the population. It wasn’t so rare for someone wearing an Austrian loden jacket to shout, Viva Franco!, and for someone else to answer Viva! in a public setting, while everyone else awkwardly pretended nothing happened.

I once loved a fascist. She wasn’t openly so, because she was a yoga instructor, but you could say it was in her blood. Her family were right-wingers with Francoist materials hidden in the corners of their home. They collected Lladró figurines, silver cutlery for special occasions, and lived by a very strict set of rules based on “tradition.” In our ten years of friendship, I visited her home often but never stayed for long. I was always terrified to make a mistake: their rules were hard for me to follow because I was from the “other side of the tracks” (I lived further away from the church than they did). She was Spanish, I merely had the passport. I went to public school and she went to catholic school. I always envied the girls who went to catholic school particularly their uniforms. I craved the objectification they received from the punk boys I hung out with when I was a tomboy leftist dirtbag…

Set in Argentina, a country still living under the long shadow of a bloody military dictatorship orchestrated by Nazi escapees, The Holy Girl by Lucrecia Martel (2004) reflects the hermetic white middle classes of Argentina through the mystical thinking of Amalia and her friends, a group of Catholic schoolgirls (often in their uniforms). I always felt deeply connected to this film because their battle with desire and shame rings true to me. Plus her name, of course. The mental gymnastics in their conversations about Catholicism remind me of when she and I talked religion. It was in one of these chats, during recess, that we realized we had taken our first communion together, many years before meeting at La Universidad Laboral, a former Fascist Phalanx compound turned High School for the Arts. God clearly wanted us to be together. It was a sign from above. We were best friends.

A perfect product of 1968, If… by Lindsay Anderson (1968) is a film about rebellion in a British boys’ school, awash in classically British self-objectification of Brittania, present in Oscar Wilde,Vivienne Westwood, and Brit Pop alike. Casting Malcom McDowell pretty much as Alex from A Clockwork Orange before Kubrick’s film even existed, If….. is an ode to homoerotic, almost Yaoi, relations as much as it is a criticism of stuffy discipline.

Perhaps you fashionably and happily believe that it’s all a simple matter of evil dictators, rather than whole populations of evil people like ourselves? Do you disagree? Don’t you find this view of history facile?

Says the teacher to his pupils, in If…, only a few minutes before scenes of bullying, hardcore spanking and “fagging” – a traditional practice in British boarding schools where younger pupils were required to act as personal servants to the eldest boys, sometimes suffering physical and/or sexual abuse.

My fascist girl never spanked me but she once disciplined me. After ten years of friendship (or was it fagging?) I committed a grave mistake: my mother had lost her apartment and I decided to stay at her place for a week. Unfortunately, there was a set of rules I had been unable to follow and one morning, at 8am, she and her mother were waiting for me in the kitchen: I deserved to be punished. I was too free, I did whatever I wanted in life and that was wrong. So they laid into me for hours. It was dark and confusing and like nothing else I’ve ever experienced. But this is what happens when you ascribe morals to etiquette.

With my tail between my legs, I cried to my other childhood friend: a goofy fun-loving leftist whose communist family had always kept their home and hearts open to me. She only had one thing to say: what else could you expect from a facha? A fascist is a fascist is a fascist. I felt stupid for thinking that my fascist could maybe have a heart.

My fascist girl had a weird relationship with her mother. It was as if she was a marionette controlled by her elder. When I read Elfriede Jelinek’s The Piano Teacher, I couldn’t help but think of her and her mother and their doomed fate. I had always been terrified of her. A supermarket fishmonger with rough hands, but as a right winger she could never see herself as part of the working class. What a strange way to live. Haneke’s The Piano Teacher (2001) does a good job of reflecting not only the heavy atmosphere of oppression I mentioned before, which in Spain we call, very accurately, rancio*, but also the obsession that fachas have with the upper classes and royalty.

Despite Isabelle Huppert’s queenly beauty, her character, Erika Kohut, will never be a sophisticate like the Klemmer family, and for that, she needs to be punished. Her sexuality is a mix of morbid voyeurism and masochistic self-mutilation because, like a good fascist, she can’t experience personal joy. If she feels any resemblance of happiness she must be stopped, redirect her attention to physical pain, and ultimately, learn to enjoy the pain. What makes this dangerous is the belief that no one else should experience joy either. When self-mutilation becomes the mutilation of others, things get sour. And wars begin.

One night, after a New Year’s Eve dinner at the home of my fascist friend, I asked her mother if I could take home a piece of leftover cake for my mom, who was home alone. She very calmly said no. If she’s not here then she doesn’t deserve it.

The Executioner by Luis García Berlanga (1963) is the only film from this series that was made under fascist rule. Unlike other writers and filmmakers that used minimalism and gloom to get past the censors, who interpreted their materials as harmless, boring works (Carmen Laforte’s Nada or Carlos Saura are good examples of this), Berlanga used satire and an endearing, relatable representation of the common folk that probably passed as inoffensively sweet to the authorities. Even though the film is obviously about the death penalty and there are many direct references to the tedium of living in Spain during the dictatorship, there’s one moment that represents falangist Spain better than any other. When the young couple goes on a picnic, they step away to flirt and dance to the popular tunes that fill the park’s air. When the owners of the radio see this, they shake their heads in disapproval and, castrating their own fun, turn the music off, get up and leave, after imparting their lesson: if you want to dance, bring your own music.