On The Bowery: The Lost and Found Films Of Sara Driver

Writer Leah Singer sits down with filmmaker Sara Driver to talk about her upcoming retrospective at Roxy Cinema New York.

Sara Driver is a thinker. She understands how ancient archetypes can shape modern stories and how the imagination can serve the lonely. As a filmmaker she brings all of it to the screen. Roxy Cinema New York presents On the Bowery: Lost and Found Films of Sara Driver from February 1st thru 8th. The Roxy will be showing You Are Not I, Sleepwalk, When Pig’s Fly, Stranger Than Paradise, and Boom For Real: The Late Teenage Years Of Jean Michel Basquiat. Driver has also chosen Stalker, Judex, and Kureneko to supplement the series as they are films that inspire her.

Sara Driver is an important female director that has paved the way for many women working in film today. Writer Leah Singer sat down with the director for a conversation regarding the retrospective at Roxy Cinema. This is an edited version of their recent interview ahead of the screenings.

LS:

I’m excited about the upcoming screenings at the Roxy. You mentioned that in 2012 Lincoln Center had a screening of your first feature Sleepwalk (1986) and you hadn’t seen it in 25 years. What’s it like to watch your own movies?

SD:

It’s very hard. I see what I did wrong. Almost every director feels that way. I think one of a directors’ worst Achilles’ heels could be that they want to re-edit their films in perpetuity.

LS:

On watching them again do they surprise you?

SD:

Well, Sleepwalk was much funnier. I remembered it as a darker film and I liked that it was humorous. I was a different person then so those films feel like they’re in a different space. Before I shot the film, Dan Talbot let me show the cast and crew Tarkovsky’s Stalker in his little theater uptown. He was the distributor of the film and everyone who worked for him was like, “Why do you want to show that it’s such a long, tedious film.” I also showed them Jacques Rivette’s Celine and Julie Go Boating. I love cinema that’s just slightly between reality and dreams.

LS:

You chose Stalker (1979) to screen as part of the series at the Roxy. I’m sure you watch your favorite films again and again. What else are you going to screen?

SD:

I’m going to show Judex (1963) by Georges Franju – I’ve only ever seen it on DVD – and Kuroneko(1968) by Kaneto Shindo. It’s another one that’s incredible to see on the big screen. Japanese ghost stories are very specific, they are based on superstitions; many of them were generated by the writer Lafcadio Hearn, who was influenced by Japanese folktales.

LS:

Were you drawn to fairytales and mythologies as a kid?

SD:

I was very into Greek and Roman mythology. I remember the moment when I realized that the gods never existed. I really thought they did until I had this revelation in fifth grade. Mythologies are what our whole sociometry is based on. When I was teaching at New York University I often felt the students were there without an anchor because they didn’t know basic storytelling, basic mythology.

LS:

You often cite a quote by the French film director Jacques Tourneur – “If you anchor your script in reality, you can go anywhere.” Does this sentiment operate as your guide?

SD:

That’s where I can get my freedom.

LS:

You shot Sleepwalk in New York. I don’t think you can make a movie in New York without recognizing its visual power. It’s a character in itself and that comes through so strongly in the film.

SD:

Scorsese’s After Hours and Sleepwalk both premiered at Cannes in 1986. I was so surprised because I didn’t know anything about After Hours. I saw all these similarities with Sleepwalk … it’s like the city was magic and everyone could feel it. Scorsese was feeling it uptown. I was feeling it downtown, and there was an echo of your emotional state on the streets at all times. I remember shooting on Crosby Street when all of a sudden my sound guy starts climbing up the fire escape of this industrial building. He went in and asked them to turn off their machines while we shot, which they did.

LS:

New York was a different place in the 1980s.

SD:

People had fled the city since the mid ’70s and the only people left were the ones who wanted to be here.

LS:

You’re screening Boom for Real (2017), a documentary you did on Jean-Michel Basquiat’s pre-fame life in New York when you didn’t need a lot of money to survive and the opinions of your peers counted more than any critics. You portray a vivid expression of community among friends at that time.

SD:

I think Boom for Real is about that community and how we instigated each other and cross-pollinated. We weren’t compartmentalized into categories of painters or musicians or filmmakers, we were all together trying different things and we were not afraid of failure. I think people have become isolated because of social media. Sitting in a room or hanging out with people is so much more conducive to generating thoughts and ideas. I was just in Portugal scouting for a new film. They’re making movies there like we did 30 years ago. They’re scrappy. Every single person who works on your crew is a filmmaker. It’s so wonderful to be with all these great creative minds and not feel limited.

LS:

In Stranger Than Rotterdam (2021), an animated short you wrote and starred in, you retell the story of how challenging it was to get financing to complete Stranger Than Paradise, a film by your partner Jim Jarmusch that you produced. How did Stranger Than Rotterdam come about?

SD:

I met the directors Noah and Lewie Kloster at a film academy hosted by Lincoln Center. They had made an animated film about the documentary filmmaker and teacher Chris Choy, my former boss at NYU and they later made one on my friend the photographer David Godlis. The story on Chris was about smuggling cigarettes and we thought maybe smuggling could be a theme for a series and I was “Oh, I have a smuggling story.” I had never told this story before.

LS:

Can you give a brief description?

SD:

In order to get the rest of the money to complete Stranger Than Paradise I was given the assignment to hand-carry Robert Frank’s Cocksucker Blues to the Rotterdam Film Festival.

LS:

Cocksucker Blues is a film that documented the 1972 Rolling Stones Exile on Main Street tour. The band didn’t want the film released because it was really raunchy and it could only be screened if Robert was present.

SD:

They were only allowed to screen it once or twice a year, that’s it, which is such a weird court decision although I think that’s been lifted since his death. It was a huge responsibility to hand-carry the film. My job at that time was to look for missing or rare films and then hand-carry them over so I could attend the festival and try to raise money for our film projects.

LS:

That’s amazing.

SD:

I remember I had to try and find all of Robert Downey Sr.’s prints.

LS:

You were a sleuth.

SD:

I was a sleuth who was a mule. A sleuth mule.

LS:

And you also had to smuggle out the 30-minute version of Stranger Than Paradise that was held captive in New York.

SD:

I can’t say who the players were who were holding it, which is one of the reasons I’ve always hesitated to tell this story. Now we’re doing a series called Blood Money, Cons, Smuggling and Schemes: the Art of Film Finance. We have a few filmmakers on board: Richard Linklater, Wes Anderson and Julie Delpy just signed on to do one. Stranger Than Rotterdam will be the first in the series. We’re fundraising for it right now.

LS:

You sent me an intriguing look book for another film you’re working on called An Odd Enchantment. I see lots of visual parallels with the fantasy/film noir genres like the use of masks and shadows and yet the underlying story attends to more benevolent concerns like caring for those who are hurting. What draws you to characters that need a hug?

SD:

I guess because I think the imagination is such a wonderful place to retreat to during trauma. I remember after 9/11 I thought I wouldn’t smile again. I went to my doctor two months later and asked, “What are you doing for people who have this kind of depression, who can’t shake this dark shadow?” She said, “I tell them to go see something they’ve never seen before, do something they’ve never done before, because it breaks the trauma loop.” And that’s what I’m doing with this character in the film. In 2015 I was at Paulo Branco’s film festival in Portugal with Laurie Anderson and Nicoletta Braschi. We were sitting at dinner and suddenly we got this news alert about the Bataclan in Paris. I will never forget the vision of these sheets being thrown out people’s windows, off their balconies, to cover the dead in the streets. We don’t see those images here. It got me thinking about massacres in America. What happens to the people who witness this stuff, many of them have trauma for the rest of their lives. They’re victims too and they’re unrecognized. So that’s where the idea was born. Then my father had Sundowners Syndrome, which is an ocular thing that happens between four o’clock and 11 with the changing of the light. He would see visions, and these visions were sometimes quite delightful. I wanted to play with a character who was on her journey toward death, but who was inside her imagination just like so many of our elders are.

LS:

How did you decide on Nicoletta Braschi as the lead?

SD:

I met Nicoletta at the same time Jim met Roberto, and then he wrote Down By Law right after that. So we’ve had a very long friendship since 1985. We always talked about doing something together. We both love tapping into our imaginations. The script came when my dad was dying. It just came out of me. Robert Desnos, the French surrealist poet was my guiding angel. He is known to have saved a whole group of people from the gas chambers by using his imagination. Nicoletta said the story was like Alice in Wonderland at the end of her life, which was such a beautiful thing to say. I hadn’t thought about it that way.

LS:

Has it been a challenge to get films made?

SD:

I remember having a retrospective in Madrid – it was before I made Boom for Real, and 20 years since I had made a film. I had all these scripts I couldn’t get made. Someone asked me, “Why is it so long between your films?” It’s a very difficult question because you don’t want to come off like a victim. I don’t feel like a victim at all. It’s the nature of the beast. We were 4% women directors in the film and television industry when they asked me that question. We’re now 11%. It’s still difficult for women directors.

LS:

I’m thinking about the artists in Colab who are in Boom for Real, that came together to do their own thing on their own terms in the late 1970s because they were shut out of the mainstream art world. Often that’s what it takes.

SD:

The one great thing about Boom For Real is that so many artists contacted me and told me the film got them back into their studios. What could be better! Lee Quiñones, one of the featured graffiti artists and I were invited to Miami Basel to screen the film. There were all these kids in the audience. I think Lee and I talked to them for an hour and a half, and they were like, “Well, how do we get our own community?” I said, the SPRING/BREAK Art Show is a great example of two kids who found an abandoned Catholic school in New York and organized curators and artists. You can do the same thing. It’s just like the Times Square Show that Colab organized in 1980.

LS:

I want to ask you about your process. How do you prepare for making a film? Do you storyboard for example?

SD:

In Sleepwalk the only thing I storyboarded was the elevator scene because we only had one floor and we had to keep repainting the elevator door. I didn’t have any money. That movie was made on 35mm and cost $200,000, which was a feat back then. But I really believe that before you make a film, you have to dream the whole thing. So I keep a journal.

LS:

What are your scripts like?

SD:

My scripts are very unusual. When people read my scripts it’s like they’ve seen a movie.

LS:

So they are highly descriptive?

SD:

I showed Lewie and Noah the script because I want to pick their brains about doing some in-camera effects. Lewie kept saying, “It’s the best movie I’ve seen this year.”

LS:

When you’re making a movie things happen. How do you reconcile your vision with the reality of happenstance?

SD:

Right, well, I had no plan for Boom For Real I let the footage tell me what it wanted and who to talk to. It all sprang from Alexis Adler’s collection of what she had saved when Jean-Michel was her roommate. I went over to her house for tea and saw the work. It was so much a poem about him and New York. I thought I would make a 20-minute celebration of the material before it gets dispersed and instead it became a feature. You have to be very present when you make a film so that you can adjust and you can be spontaneous, because creativity is about being spontaneous.

LS:

What are you looking forward to in 2023?

SD:

Being instigated and instigating people. I have three projects going right now. I feel like I’m coming out of a long sleep. The world has felt like it’s imploding and exploding at the same time. There’s a lot of cultural fascism going on which I don’t know how to navigate and I hope it ends. I look forward to hearing a lot of live music, which feeds my soul, and seeing a lot of great art. And it’s so great to go back to the movies.

Words By Leah Singer

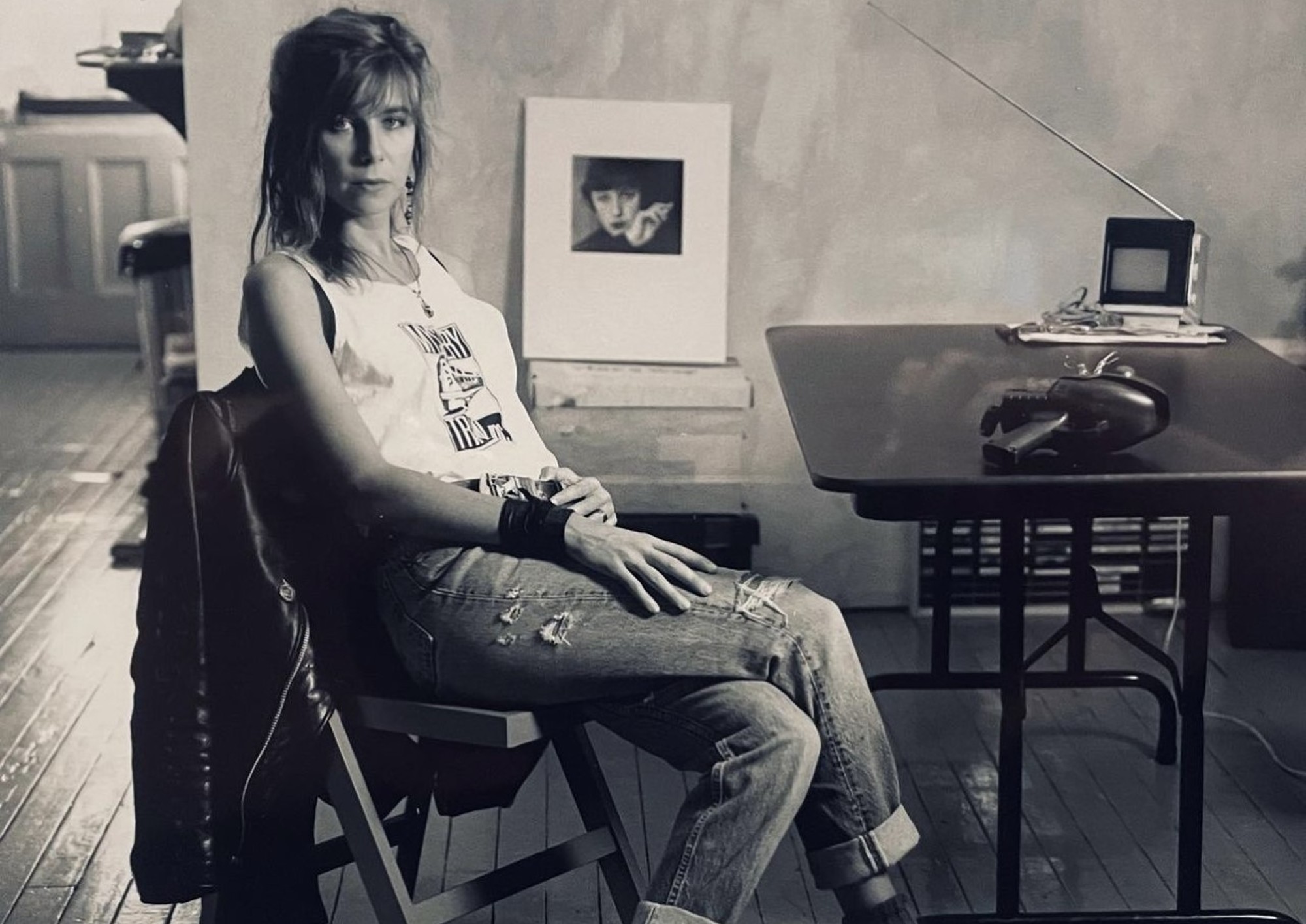

Portrait of filmmaker Sara Driver. Photo by Kate Simon